Most fossil fuel companies have increased emissions since the Paris Agreement

A majority of fossil fuel companies produced more emissions in the seven years after the signing of the Paris Agreement than in the seven years before, new data shows.

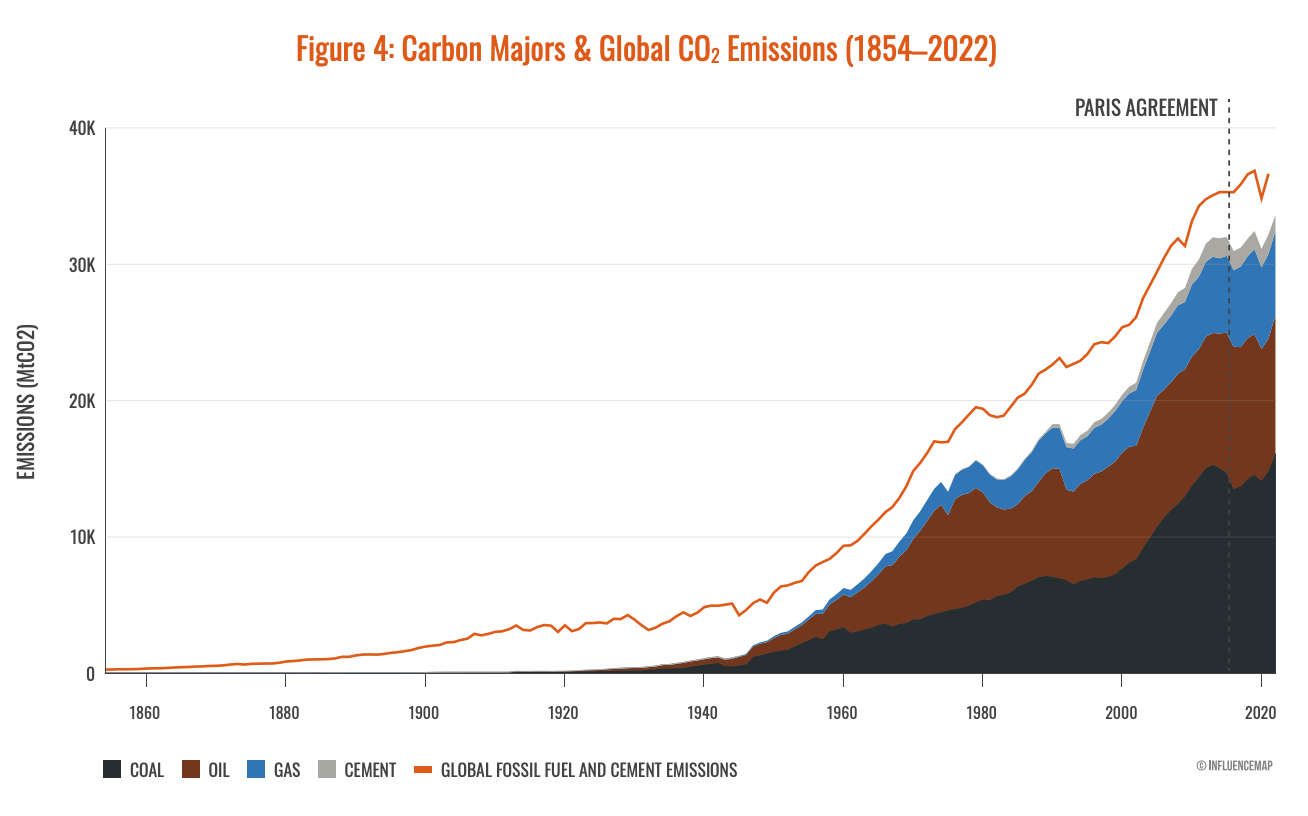

The Carbon Majors Database, released today by think tank InfluenceMap, quantifies the emissions attributed to the 122 largest oil, gas, coal and cement suppliers, both from production and from combustion.

It reveals that 80% of the 251 gigatonnes of CO2e emitted between 2016 and 2022 can be traced to just 57 corporate and state-producing entities, led by China’s coal activities, Saudi Aramco, Gazprom, India’s coal and the National Iranian Oil Company.

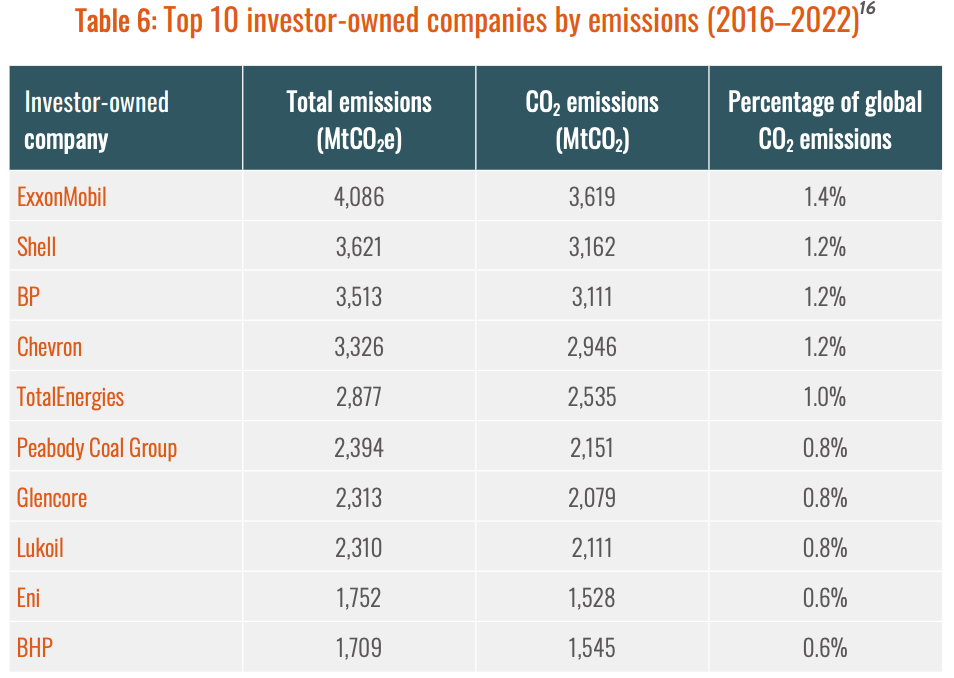

Of these, 62 gigatonnes (21.6% of total fossil fuel and cement emissions) are attributed to investor-owned companies, led by ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron and TotalEnergies. Of 66 companies active from 2009 to 2022, 36 (55%) have increased emissions since the Paris Agreement.

Lack of action from oil and gas companies

Oil and gas majors recently came under fire from investor groups and financial think tanks for their “insufficient” transition plans, as none of the 10 Western oil majors analysed by Climate Action 100+ have emissions reduction targets aligned with a 1.5ºC scenario.

Despite this evidence, oil and gas producers have repeatedly lowered their climate ambitions, with Shell earlier this month reducing its carbon intensity reduction goal from 20% to a “15-20%” for 2030. In the US, ExxonMobil is even suing some of its own investors to block them from submitting climate proposals at its AGM.

“The Carbon Majors database is a key tool in attributing responsibility for climate change to the fossil fuel producers with the most significant role in driving global CO2 emissions. InfluenceMap’s new analysis shows that this group is not slowing down production, with most entities increasing production after the Paris Agreement. This research provides a crucial link in holding these energy giants to account on the consequences of their activities,” said Daan Van Acker, Program Manager at InfluenceMap.

Increased transparency (and climate litigation)

The database is likely to be used by governments, academics and NGOs to increase transparency around climate action and hold large polluters to account. According to Reuters, a previous version has been used in an ongoing court case in which a Belgian farmer is seeking damages from TotalEnergies for climate-related damages to his farm.

Shell is currently appealing a 2021 Dutch court ruling that ordered it to reduce its carbon footprint by 45% by 2030 from 2019 levels – including emissions related to the combustion of its products, while Woodside Energy is being sued by Greenpeace Australia for claiming to reduce emissions simply based on offsets, while actual emissions rose.

The increased transparency brought about by the Carbon Majors database will support the climate litigation cases of activists looking to force energy companies to transition to a low-carbon business model.

“We actually have a lot of very related lawsuits in almost every region of the world now, and I think for a Chief Sustainability Officer or general counsel within companies, the lesson is going to be that they will need to be much more risk-averse, when they're deciding what and how to set emission reduction targets,” Todd Cort, Faculty Co-Director for the Yale Center for Business and the Environment, who serves on a number of sustainability advisory boards, tells CSO Futures.

According to him, improved scenario analysis and financial risk due diligence will be necessary to win the kind of appeal Shell is now arguing: “Companies are going to want to come to the table with much more evidence on what the financial implications of a more aggressive timeline are.”

Member discussion